New rules went into effect on February 13, 2020, that implemented the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), expanding the authority of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), the US agency that reviews foreign investments in the US for potential national security concerns.

New rules went into effect on February 13, 2020, that implemented the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), expanding the authority of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), the US agency that reviews foreign investments in the US for potential national security concerns.

The new rules include CFIUS authority over certain transactions that involve property rights in airports or maritime ports. In this blog post, we summarize these new authorities relating to airports and maritime ports and provides insight into how investors and operators impacted by these authorities can account for CFIUS regulatory risks going forward.

Rules Applying CFIUS Jurisdiction Over Transactions Involving Property Rights in Airports/Maritime Ports

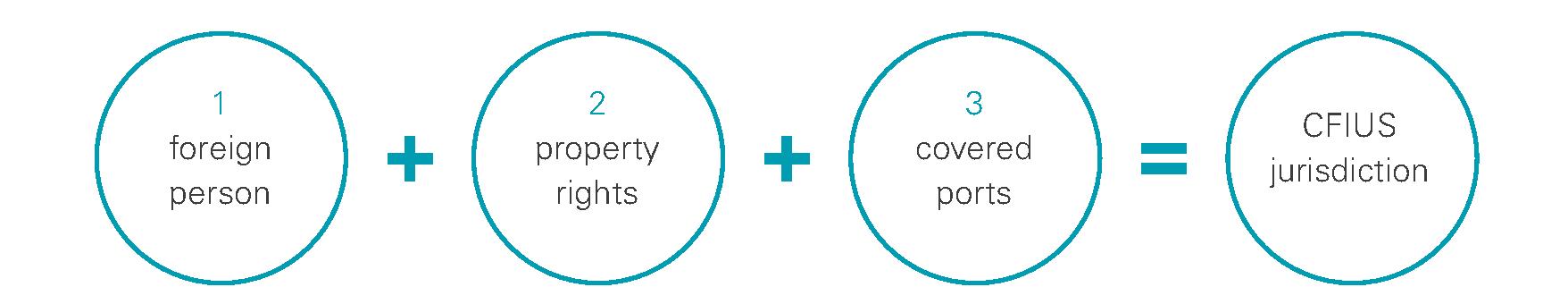

FIRRMA expanded CFIUS authority over transactions that involve the “purchase or lease by, or a concession to, a foreign person” of real estate that “is located within, or will function as part of, an air or maritime port . . .” The new rules implementing this FIRRMA provision capture any transaction that results in a “foreign person” having at least three enumerated “property rights” in specific airports and maritime ports – defined as “covered ports.” Unlike CFIUS authority over foreign person acquisitions of control in a US business, this new authority is triggered by transactions conferring or changing property rights regardless of whether a business is being acquired.

- A foreign person is any non-US government, national, or legal entity organized under non-US laws if either its principal place of business is outside the US or its equity securities are primarily traded on a foreign exchange. Importantly, this criteria could be satisfied with only a minority non-US participation or a non-US business partner, provided that the foreign person could gain any three of the relevant property rights. For the purposes of this expanded CFIUS authority over real estate transactions, the CFIUS regulations “except” certain foreign persons from the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada.

- The following property rights are relevant to this assessment, whether or not exercised or shared with other persons, and whether or not the underlying real estate is subject to an easement or other encumbrance:

- To physically access the real estate

- To exclude others from physically accessing the real estate

- To improve or develop the real estate

- To attach fixed or immovable structures or objects to the real estate

- Covered ports include the following airports and maritime ports. A complete list of the US airports and maritime ports that fall within the definition of covered ports, as of the time of this blog post, is here.

- Airports listed a large hub airports as determined annually by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

- Airports handling greater than 1.24 billion pounds of cargo as determined annually by the FAA

- Airports designed by as joint civilian/military (“Joint-Use”) airports by the FAA

- Maritime ports designated as a commercial strategic seaport within the National Port Readiness Network.

- Maritime ports rated as either a top 25 tonnage, container, or dry bulk port as determined by the Maritime Administration

Broad Implications for Businesses That Operate Within Ports, or Investors in Such Businesses

Businesses with operations within ports will generally have property rights that could trigger CFIUS authority. The obvious case is a company that provides port management services, however, many types of businesses acquire property rights at port facilities as part of their operations. For example, a parking operator may have sufficient property rights concerning the on-airport parking facilities that it manages, rental car agencies may have sufficient property rights relating to their on-airport office and service areas, and even hospitality establishments could fall within this jurisdiction. Given the broad implications of CFIUS jurisdiction related to covered ports, affected businesses and investors should keep in mind the following regulatory risk areas:

- New business partners can implicate CFIUS authority. When entering into new business partnerships that could involve foreign persons, consider whether that new relationship is subject to CFIUS authority and which party bears the risks associated with any CFIUS action.

- Changes to rights can re-implicate CFIUS authority. For businesses already having foreign ownership or control, consider that restructurings, contract renewals, lease extensions, or other types of changes could implicate or re-implicate CFIUS authority over situations that may be pre-existing or may have already received CFIUS clearance.

- Consider how to allocate the CFIUS regulatory risk. This applies to transactions whether or not they are seeking to obtain CFIUS clearance (see discussion below about obtaining a CFIUS safe harbor). If parties are not seeking CFIUS clearance, consider how the parties should allocate the risk and burdens associated with a potential CFIUS review in the future; alternatively, if parties are seeking clearance, consider how the parties can allocate the costs and risks of a potentially adverse finding by CFIUS.

- With COVID-19 impacts, defaults on loan obligations could implicate CFIUS authority. Given the economic impact of COVID-19, lending institutions with foreign person ownership or control should consider whether a default under a lending transaction could trigger CFIUS authority.

Assessing CFIUS Risks and Determining Whether to Seek Safe Harbor Protection

If CFIUS authority is implicated, CFIUS has the authority to investigate the relevant transaction, even after closing. This adds uncertainty to deals because of the future potential risk of CFIUS regulatory action that could impact the value of the transaction. For example, CFIUS could impose mitigation requirements or seek a divestiture. To remove this uncertainty parties have the option of submitting a voluntary notice or declaration about the transaction to CFIUS for review and, if CFIUS finds no national security concerns with the transaction following the review (i.e., CFIUS clears the transaction), the transaction enters a safe harbor: CFIUS cannot re-review a transaction that is previously cleared absent some material omission or misrepresentation that led to the clearance. Of course, preparing a filing and seeking clearance from CFIUS can add time and costs to any transaction. Parties to a transaction that is subject to CFIUS authority can seek an abbreviated risk assessment from experienced CFIUS counsel to help guide the business decision of whether to proceed with seeking CFIUS clearance.

Keep in mind: investments with direct/indirect foreign state-ownership might have mandatory CFIUS filing requirements

Note, this post focuses on the broad CFIUS authority that FIRRMA created under the real property provisions applicable to covered ports. In addition to this broad authority, however, the new CFIUS rules also created a mandatory filing requirement if any investor, having 49% ownership directly or indirectly by a foreign state (including as a limited partner), makes an investment of 25% or more in any business that owns or operates a covered port.

Please contact our team with any questions.